17.2. The Optim.jl Package#

While building our own gradient descent and Newton methods is great for learning, practical applications require professional, optimized tools. In Julia, the Optim.jl package provides several high-performance optimizers.

It saves us from having to manually implement:

Robust line searches (e.g., Wolfe conditions)

Hessian approximations (quasi-Newton methods)

Trust-region methods

Stopping criteria (convergence checks)

We can simply provide our objective function f and, optionally, our gradient g and Hessian h. Optim.jl will then select an appropriate powerful algorithm to find the minimum.

using Optim, Plots

# First include all functions from the previous section

using NBInclude

@nbinclude("Gradient_Based_Optimization.ipynb");

Path 1: Length=501, ||gradient|| = 1.4715843307921153

Path 2: Length=67, ||gradient|| = 8.918594790414185e-5

Path 3: Length=501, ||gradient|| = 1.7575802156689104

Path 1: Length=47, ||gradient|| = 7.870693265014514e-5

Path 2: Length=19, ||gradient|| = 2.707659519760321e-5

Path 3: Length=34, ||gradient|| = 6.996634619625889e-5

Path 1: Length=47, ||gradient|| = 7.870696143799702e-5

Path 2: Length=19, ||gradient|| = 2.7076774319819133e-5

Path 3: Length=34, ||gradient|| = 6.996618451764213e-5

Path 1: Length=5, ||gradient|| = 2.4554302167287822e-6

Path 2: Length=4, ||gradient|| = 1.2227294235742997e-5

Path 3: Length=6, ||gradient|| = 1.75484871960624e-8

17.2.1. Method 1: Derivative-Free Optimization#

In the simplest case, we can provide only the function f and a starting point x0.

Optim.jl will automatically select a 0-th order (derivative-free) method, like Nelder-Mead. This is a great option when your function’s gradient is unknown, complex, or undefined.

# Our starting point

x0 = [0.0, 1.0]

# Call optimize with only the function and start point

result_nm = optimize(f, x0)

# The output shows it found a minimum using the Nelder-Mead algorithm.

* Status: success

* Candidate solution

Final objective value: -2.072854e-01

* Found with

Algorithm: Nelder-Mead

* Convergence measures

√(Σ(yᵢ-ȳ)²)/n ≤ 1.0e-08

* Work counters

Seconds run: 0 (vs limit Inf)

Iterations: 34

f(x) calls: 66

17.2.2. Method 2: First-Order (Gradient) Optimization#

If we provide the gradient, Optim.jl can use a much more powerful 1st-order method. It will automatically select L-BFGS, a famous quasi-Newton method. This is like our gradient descent, but it cleverly builds an approximation of the Hessian using only gradient information, making it converge much faster.

# Define our gradient function (using our numerical version)

g(x) = finite_difference_gradient(f, x)

# Call optimize with f, g, and x0

result_lbfgs = optimize(f, g, x0; inplace=false)

# The output shows it used L-BFGS and took far fewer iterations than Nelder-Mead.

* Status: success

* Candidate solution

Final objective value: -1.000000e+00

* Found with

Algorithm: L-BFGS

* Convergence measures

|x - x'| = 4.31e-06 ≰ 0.0e+00

|x - x'|/|x'| = 8.04e-07 ≰ 0.0e+00

|f(x) - f(x')| = 1.36e-11 ≰ 0.0e+00

|f(x) - f(x')|/|f(x')| = 1.36e-11 ≰ 0.0e+00

|g(x)| = 6.88e-10 ≤ 1.0e-08

* Work counters

Seconds run: 0 (vs limit Inf)

Iterations: 7

f(x) calls: 20

∇f(x) calls: 20

17.2.3. Method 3: Second-Order (Hessian) Optimization#

If we can provide the Hessian, Optim.jl will use a full 2nd-order method, like NewtonTrustRegion. This is a robust version of the Newton’s method we built. It uses the full curvature information (the Hessian) to take very direct, fast steps to the minimum.

# Define our Hessian function (using our numerical version)

h(x) = finite_difference_hessian(f, x)

# Call optimize with f, g, h, and x0

result_newton = optimize(f, g, h, x0; inplace=false)

# This is very fast, converging in only a few steps.

* Status: success

* Candidate solution

Final objective value: -2.072854e-01

* Found with

Algorithm: Newton's Method

* Convergence measures

|x - x'| = 2.51e-05 ≰ 0.0e+00

|x - x'|/|x'| = 2.96e-05 ≰ 0.0e+00

|f(x) - f(x')| = 2.16e-10 ≰ 0.0e+00

|f(x) - f(x')|/|f(x')| = 1.04e-09 ≰ 0.0e+00

|g(x)| = 7.38e-10 ≤ 1.0e-08

* Work counters

Seconds run: 0 (vs limit Inf)

Iterations: 5

f(x) calls: 18

∇f(x) calls: 18

∇²f(x) calls: 5

17.2.4. Method 4: Automatic Differentiation (The Best of All Worlds)#

Manually writing g and h (even our numerical versions) is work. The best solution is often to use Automatic Differentiation (AD).

We can just pass autodiff=:forward to optimize. Optim.jl will automatically analyze our code for f and generate the exact gradient and Hessian functions for us, all at machine speed. It then uses this information to automatically select a powerful 2nd-order method.

# Call optimize using forward-mode automatic differentiation

# We ONLY provide f and x0!

result_ad = optimize(f, x0, autodiff=:forward)

# Look at the output: Optim.jl was ableto use the 'NewtonTrustRegion' method

# because it generated the gradient and Hessian itself!

# This gives us the power of Newton's method with the simplicity of Nelder-Mead.

* Status: success

* Candidate solution

Final objective value: -2.072854e-01

* Found with

Algorithm: Nelder-Mead

* Convergence measures

√(Σ(yᵢ-ȳ)²)/n ≤ 1.0e-08

* Work counters

Seconds run: 0 (vs limit Inf)

Iterations: 34

f(x) calls: 66

This also works for the Hessian matrix in Newton’s method. Note the extremely fast convergence (number of iterations):

result_newton_ad = optimize(f, x0, Newton(), autodiff=:forward)

* Status: success

* Candidate solution

Final objective value: -2.072854e-01

* Found with

Algorithm: Newton's Method

* Convergence measures

|x - x'| = 2.50e-05 ≰ 0.0e+00

|x - x'|/|x'| = 2.95e-05 ≰ 0.0e+00

|f(x) - f(x')| = 2.14e-10 ≰ 0.0e+00

|f(x) - f(x')|/|f(x')| = 1.03e-09 ≰ 0.0e+00

|g(x)| = 7.31e-10 ≤ 1.0e-08

* Work counters

Seconds run: 0 (vs limit Inf)

Iterations: 5

f(x) calls: 18

∇f(x) calls: 18

∇²f(x) calls: 5

Finally, we use the BFGS solver using automatic differentiation. This is a widely used method, since it obtains convergence comparable to Newton’s method but without requiring explicit Hessian matrices:

result_bfgs_ad = optimize(f, x0, BFGS(), autodiff=:forward)

* Status: success

* Candidate solution

Final objective value: -1.000000e+00

* Found with

Algorithm: BFGS

* Convergence measures

|x - x'| = 1.70e-07 ≰ 0.0e+00

|x - x'|/|x'| = 3.18e-08 ≰ 0.0e+00

|f(x) - f(x')| = 2.12e-14 ≰ 0.0e+00

|f(x) - f(x')|/|f(x')| = 2.12e-14 ≰ 0.0e+00

|g(x)| = 1.18e-12 ≤ 1.0e-08

* Work counters

Seconds run: 0 (vs limit Inf)

Iterations: 7

f(x) calls: 22

∇f(x) calls: 22

17.2.5. Visualizing Optim’s Iterations#

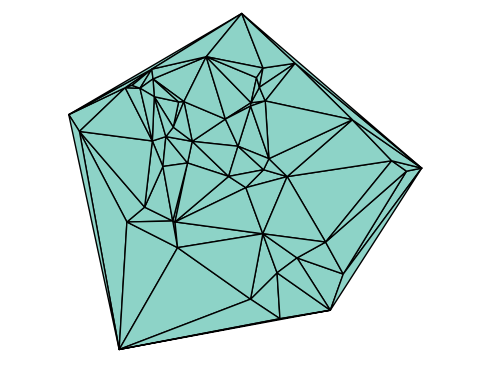

Just like with our manual optimizers, Optim.jl will find different local minima depending on the start point. We can ask the solver to store_trace=true to record its path, and then plot it on our contour map.

# Note: The optimizer will jump outside out initial domain

# Plot a larger domain to see these new minima

fplot(f, xlim=(-5,5), ylim=(-6,1.5), levels=10)

plot!(title="Optim.jl (L-BFGS) from Different Starts")

# The same starting points from our manual notebook

x0s = [[-2.0, -0.5], [0.0, 1.0], [2.0, -1.0]]

for (i, x0) in enumerate(x0s)

# We'll explicitly choose Newton and ask it to save the trace

res = optimize(f, g, x0,

method=LBFGS(),

store_trace=true,

extended_trace=true,

inplace=false)

# Extract the path from the trace object

# The trace is a vector of states; we get the position 'x' from each state's metadata

xs = [s.metadata["x"] for s in res.trace]

# Plot the path

plot_path(xs, label="Path $i")

# Print the final position (the 'minimizer')

println("Path $i: Length=$(length(xs)), ||gradient|| = $(sqrt(sum(∇f(xs[end]).^2)))")

end

plot!()

# Note that Path 2 and 3 "jumped" to different minima

Path 1: Length=8, ||gradient|| = 3.287736589951257e-10

Path 2: Length=8, ||gradient|| = 9.328012128983552e-10

Path 3: Length=8, ||gradient|| = 1.6690603046630815e-10